Gender equality is usually considered one of the major forms of ‘diversity and inclusion’. Universities have diversity and inclusion programmes, as do large corporations, governments, and pretty much any formal grouping of people that wishes to codify their approach to underrepresented groups within a particular environment. Diversity is often celebrated as a proxy for equality (for example, hiring an equal number of women to men, or having a STEM course represent an equal female-male split). This blog post argues that this approach is insufficient, and that without well-thought out and robust inclusion programmes, diversity by itself will achieve little. Placing colleagues from underrepresented groups into a non-welcoming, non-inclusive environment sets them up to fail and fails to achieve sustainable meaningful representation.

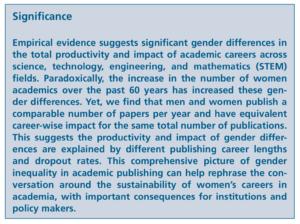

The failure of inclusion programmes currently is highlighted in a recent study of female scientists in academia. Examining gender inequality across countries and disciplines, a group of researchers found that drop-out rates significantly decrease women’s contributions to the field[1]. More specifically, female academics were found to be 19.5% more likely to leave academia every year compared to their male counterparts. This results in a major significant advantage for male researchers, as despite the number of women increasing over the last 60 years, and despite relative publishing volumes being comparable in number, ultimately females make less of an imprint in their respective fields, as males stay in the field, submitting more research as their careers continue to develop. The issue here is shown through this study to be largely a problem surrounding the retention of female academics. The authors summarise their research findings as follows:

Fig 1: From Huang et al, reference 1.

Fig 1: From Huang et al, reference 1.

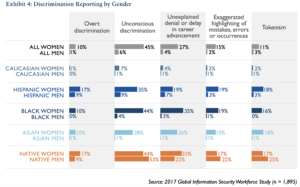

The challenges in retaining talent from underrepresented groups is not limited to academia. Non-profit organisation ISC2 surveyed over 9,000 information security colleagues, summarising their findings a 2018 report titled ‘Innovation Through Inclusion: The Multicultural Cybersecurity Workforce’[2]. They found significant barriers to entry and advancement in the workplace for underrepresented practitioners including disenfranchisement and discrimination. To quote the results through the following excerpt:

‘Across all races and ethnicities, women experience greater rates of discrimination in the workplace than men, reporting discrimination in much greater proportions than men when viewed as a total U.S. population. Women who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian or of Native American descent, report the highest numbers of discrimination.’

Such discrimination, coupled with pay discrepancies also noted in the report, create an uncomfortable environment in which to work. LeClair, Shih and Abraham (2014) suggest ‘climate dissatisfaction, pay inequity, pressure from family issues, gender discrimination, lack of social change, lack of support from employers for advancement’ as contributing reasons that encourage women to leave[3]. While hiring practices might reflect diversity strategy targets, looking at retention over time can give a much stronger indicator of how an environment treats underrepresented groups. In the case of information security, ISACA reports a ‘dismal’ retention rate with 44% of women leaving the field mid-career[4].

Fig2. Discriminating reporting by gender, see reference 2. ‘For the purposes of this study, discrimination can take the form of unfair treatment based on gender, age, ethnicity or an employee’s cultural group. The results of the survey reveal that discrimination is most prevalent along two intersecting axes, ethnicity and gender.’

Fig2. Discriminating reporting by gender, see reference 2. ‘For the purposes of this study, discrimination can take the form of unfair treatment based on gender, age, ethnicity or an employee’s cultural group. The results of the survey reveal that discrimination is most prevalent along two intersecting axes, ethnicity and gender.’

Online discussions around the topic of diversity and inclusion have voiced concerns about how diversity is often seen as a ‘tokenism’ target, attracting and taking on women as an achievable and public-relations-friendly achievement, with less effort into actually ensuring the workplace culture and power dynamics are structured in a way that does not disadvantage women. Diversity is an essential objective, of course, and it is known that due to systemic issues in sexism and other forms of discrimination, initiatives including CodeFirst: Girls and #WomenInStem, and Ada Lovelace Day can all do incredibly valuable work in engaging talent. That does not mean diversity is sufficient. Retention strategy should be a major consideration by academia and industry. Equal opportunities should not mean getting a diverse number of candidates to a STEM degree, or graduate programme. It should be about making sure that all those who have the talent, ability and enthusiasm for a field should feel welcome there. It should be about making sure that discrimination of any form, in any environment should be managed swiftly, with a genuine culture that encourages talent to stay. Women should not be promoted into positions where they will fail, or made to feel like an outsider. Initiatives such as mentorship programmes[5], shared parental leave, and a consistent focus on an inclusive culture[6] (reiterated by senior colleagues) are just a few of the ways in which inclusion can be designed into a workplace.

This same argument – and proposal – may be made when speaking about any minority group, whether that is gender, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, access needs – the list goes on. By showing that an environment is more than the physical presence of diversity, we can highlight the value of inclusion and draw attention to the sustainability of diversity as a women’s (or any minority’s) career progresses. Our research, work environments, and wellbeing will all be richer as a result.

[1] Huang, J., Gates, A.J., Sinatra, R. and Barabási, A.L., 2020. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/02/14/1914221117

[2] ISC2 White Paper, (2018). Innovation Through Inclusion: The Multicultural Cybersecurity Workforce. [online] Available at: https://www.isc2.org/-/media/Files/Research/Innovation-Through-Inclusion-Report.ashx

[3] Peacock, D. and Irons, A., 2017. Gender inequality in cybersecurity: Exploring the gender gap in opportunities and progression. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 9(1), pp.25-44.

[4] Reducing the Gender Disparity in Cyber Security. Available at: https://www.isaca.org/resources/news-and-trends/isaca-now-blog/2016/reducing-the-gender-disparity-in-cyber-security

[5] CSO Online: Women in security: Cultures, incentives that promote retention. Available at: https://www.csoonline.com/article/2992461/women-in-security-cultures-incentives-that-promote-retention.html

[6] DarkReading: Best Practices for Recruiting & Retaining Women in Security. Available at: https://www.darkreading.com/careers-and-people/best-practices-for-recruiting-and-retaining-women-in-security/d/d-id/1331114

Amy Ertan, PhD student